The first I heard of this very interesting story came from Patrick Kowalczyk in 2006 when I was doing some physical work on Woodside.

Patrick told me of a program he remembered seeing on Channel 9 some years earlier that dealt with graft and corruption in large cities around 1900. What stood out to Patrick was a political cartoon from that era depicting a fat cat politician. Displayed somehow in the cartoon were names Patrick, a letter carrier, couldn’t help but recognize. They were the names of several of the streets around Woodside. Two of those he remembered were Folk and Jerome.

I was curious but this information meant nothing to me at the time. Sometime later, while my wife and I were waiting for a table at the Bottleworks, I picked up a book from their bookshelf in the waiting area. The book was “Seeking St. Louis” edited by Lee Ann Sandweiss. In the center of the book was an essay by a man named Wetmore that contained much of the information of the situation Patrick had seen referenced in the cartoon.

OK, here goes. Frank Butler, a Democratic Party boss, who had arrived in St. Louis as a poor Irish immigrant in 1857, was a multi-millionaire by 1900. His path from rags to riches was accomplished through public horseshoeing contracts and later contract garbage hauling. Frank was a fixer who collected bribes from businessmen who were part of a group known as the “Big Cinch”. He then redistributed the wealth amongst select office holders in the city’s Municipal Assembly, forerunner of the Board of Alderman.

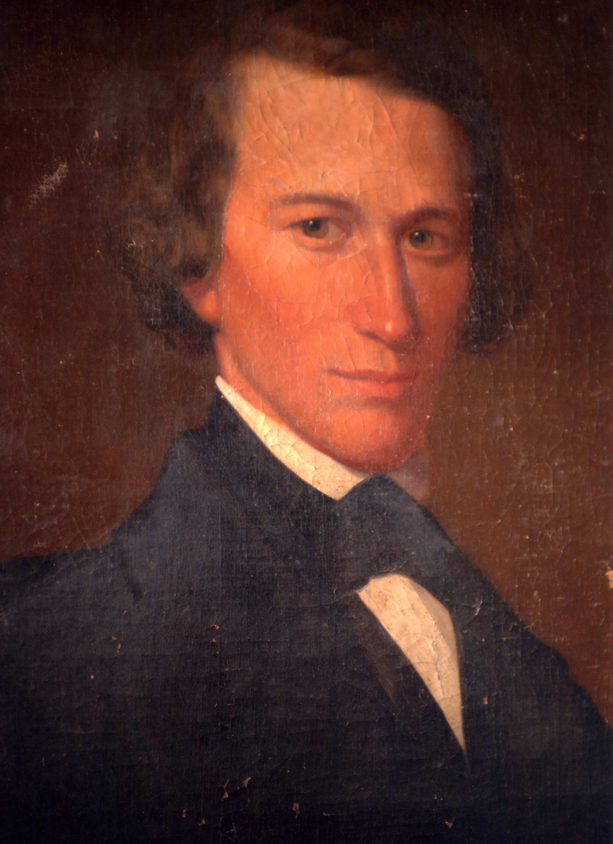

Joseph W. Folk, from Tennessee, was a fast-rising, young Democratic lawyer who gained attention by negotiating a settlement with striking streetcar workers. After managing to be nominated for and then winning election to the office of circuit attorney, (prosecutor for the City of St. Louis), “Holy Joe” began investigating reports of bribe-taking and corruption in City Hall.

In 1902, he won a conviction against Frank Butler for attempting to bribe two members of the Board of Health so he could keep his garbage contract. Much to the consternation of the party officials who helped him get elected, Folk scrambled much of the corruption through indictments and trials with his “Missouri idea” of virtuous politics from 1901 through 1904. In 1904, he was elected Governor of the State of Missouri.

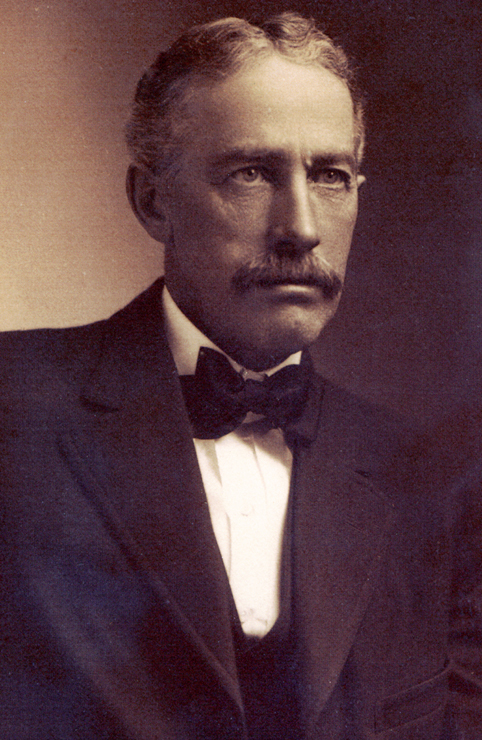

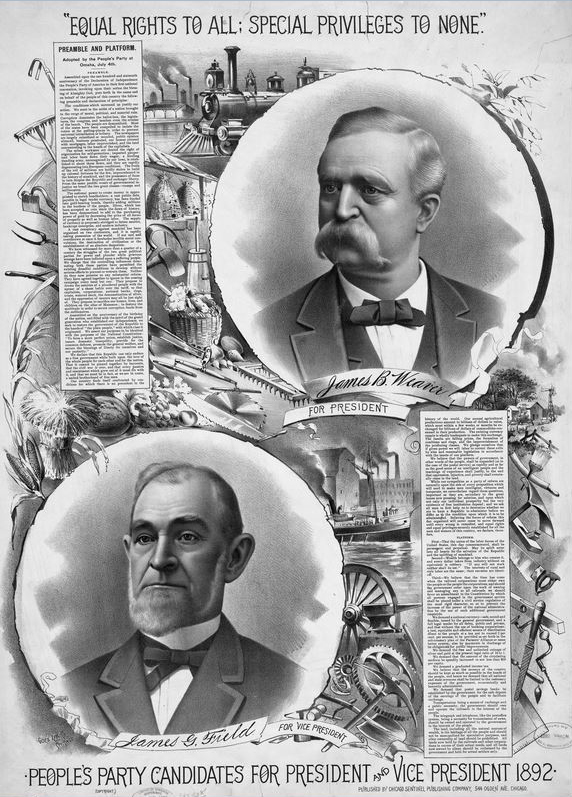

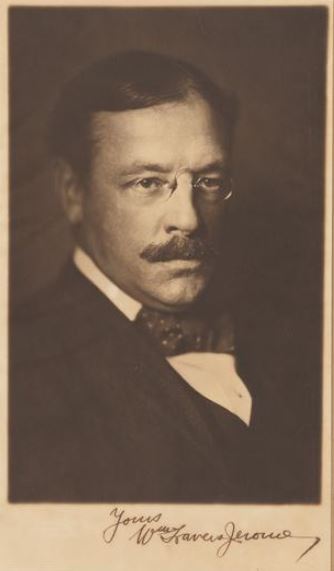

So how did the streets around Woodside come to be named for Folk, and I think, William T. Jerome, a district attorney of New York City and Gen. James B. Weaver, once a Populist candidate for president, from Iowa? I speculate they were named by Circuit Judge Edward “Ned” Rannells, son of Charles Rannells, builder of Woodside. Ned subdivided the family farm. It seems likely he paid homage to these men who he admired by naming the streets after them. From his position as a circuit judge he may have known them professionally if not personally as well.

My conclusion involves a bit of speculation but I’d be willing to bet further investigation will confirm that these three streets are named for the aforementioned men. Ned is the fellow most likely to have done it.

The Museum of the City of New York

My friend Richard Rubin had mentioned that there is a primary street in the Bronx named Jerome Avenue; he wondered if there might be a connection. I told him about the news you uncovered and he did some further research himself. What he found is this: That the Jerome Avenue in the Bronx was named after Leonard Jerome, the grandfather of Winston Churchill. Jerome Avenue in Maplewood was, as you say, named after his nephew, William T Jerome, who was instrumental in routing corruption in New York City. William Jerome was therefore a cousin of Churchill’s mother!

So proud of my street namesake! Thank you for this most interesting info! –and for the Harper Pharmacy photos==so beautiful! a treasure!!!

Familiar stories of corruption and reform. They keep playing out in different ways throughout our history at every level from national to local. I guess that means that reformers will never be able to say, “job done!” and move on to retirement with a clean conscience. But on the other hand, reforming can always be counted on to provide a steady stream of employment opportunities. Good to know that Maplewood’s streets are named for some of the good guys. I want to be on the side that has Mark Twain on the team.

Well put, Dan. Thanks.

Much thanks to both of the folks who took the time to comment and add detail. This is a complicated story that must be condensed a great deal to fit this space, of course. Additionally we’ve had a bit of trouble with our interface. Things jump around a bit between my final edit and them showing up here. I’ve got most of it straight now so I’m going to leave it alone. The credit for the Jerome photo is incorrect. It should be The Museum of the City of New York.

Additionally I have an interesting quote from Mark Twain speaking at a dinner at Delmonico’s for Mr. Jerome on May 8,1909. Introduced as the last word on all public questions and public men, Mark Twain, who was one of the committee to arrange for the dinner, said in part:

“Indeed, that is very sudden. I was not informed that the verdict was going to depend upon my judgment, but that makes not the least difference in the world, when you already know all about it. It is not any matter when you called upon to express it; you can get up and to it, and my verdict has already been recorded in my heart and in my head, as regards Mr. Jerome and his administration of the criminal affairs of this county.

“I voted for Mr. Jerome in those old days, and I should like to vote for him again, if he runs for any office. [Applause.] I moved out of New York, and that is the reason, I suppose, I cannot vote for him again. There may be some way, but I have not found it out. But now, I am a farmer, a farmer up in Connecticut, and winning laurels. Those people already speak with such high favor, admiration, of my farming, and they say that I am the only man that has ever come to that region who could make two blades of grass grow where only three grew before. [Laughter.]

“Well, I cannot vote for him. You see that. As it stands now, I cannot. I am crippled in that way and to that extent, for I would ever so much like to do it. I am not a Congress, and I cannot distribute pensions, and I don’t know any other legitimate way to buy a vote. [Laughter.] But if I should think any legitimate way, I shall make use it, and then I shall vote for Mr. Jerome.” The New York Times

Always enjoyable, Doug. I will drive down those streets with renewed respect that they are not named after wealthy people from our past, but rather folks who fought against corruption and for justice. I like that.

Claude Wetmore was an investigative reporter for the Post-Dispatch who often collaborated with Lincoln Steffens of McClure’s Magazine. You can read more about the Big Cinch in Steffens’s book “The Shame of the Cities.” For more on Joseph Folk read “Holy Joe : Joseph W. Folk and the Missouri idea”

by Steven L Piott.

Comments are closed.