In his landmark 1911 History of Saint Louis County – Missouri, WLT devoted Chapter IX to The Civil War Period in St. Louis County. On page 105 in a section titled, “Slavery in the County”, he wrote, “Many families owned slaves; a great many did not. So far as our personal knowledge extends we never knew or heard of ill-treatment of slaves in the part of the county that was outside the city. The white boys played with the black ones, went a fishing with them in numerous instances, pulled weeds, hoed potatoes and shared in their tasks. Both men and women were treated with kindness and accorded many privileges. In most cases they were careless and happy, although, of course, the desire for freedom began to become more manifest the nearer we approached to the Civil war. The pathetic feature of slavery, one that had an appealing influence upon all properly constructed minds and hearts, was the tearing apart of the negro man and his wife, the separations (that we read about) of the mother and the child. The writer never had personal knowledge of cases of this nature among the slave holding families of St. Louis county.

The attachments that began in slavery days between the two races were not severed by the war. Numerous instances can be cited of the return, after a few month’s absence, of the freed negro man and woman to the old home; of continued residence therein after the war; of death and burial surrounded and attended with love and respect.”

WLT then gives four examples that illustrate the points he was making. He then writes, “We are indebted for this information to Ben Hughes, a colored resident of Maplewood, whose father and mother both belonged to the Bompart family on the Manchester Road.

In 1861, the Home Guards made a raid upon the Southern sympathizers of the county, took their slaves with them back to the city, incidentally depopulating, as men will, under such circumstances, the chicken houses, and creating excited indignation.” Like the removal of the slaves did not? The removal of the slaves so early in the war is a detail I had not heard before. The city was still part of the county when this incident occurred.

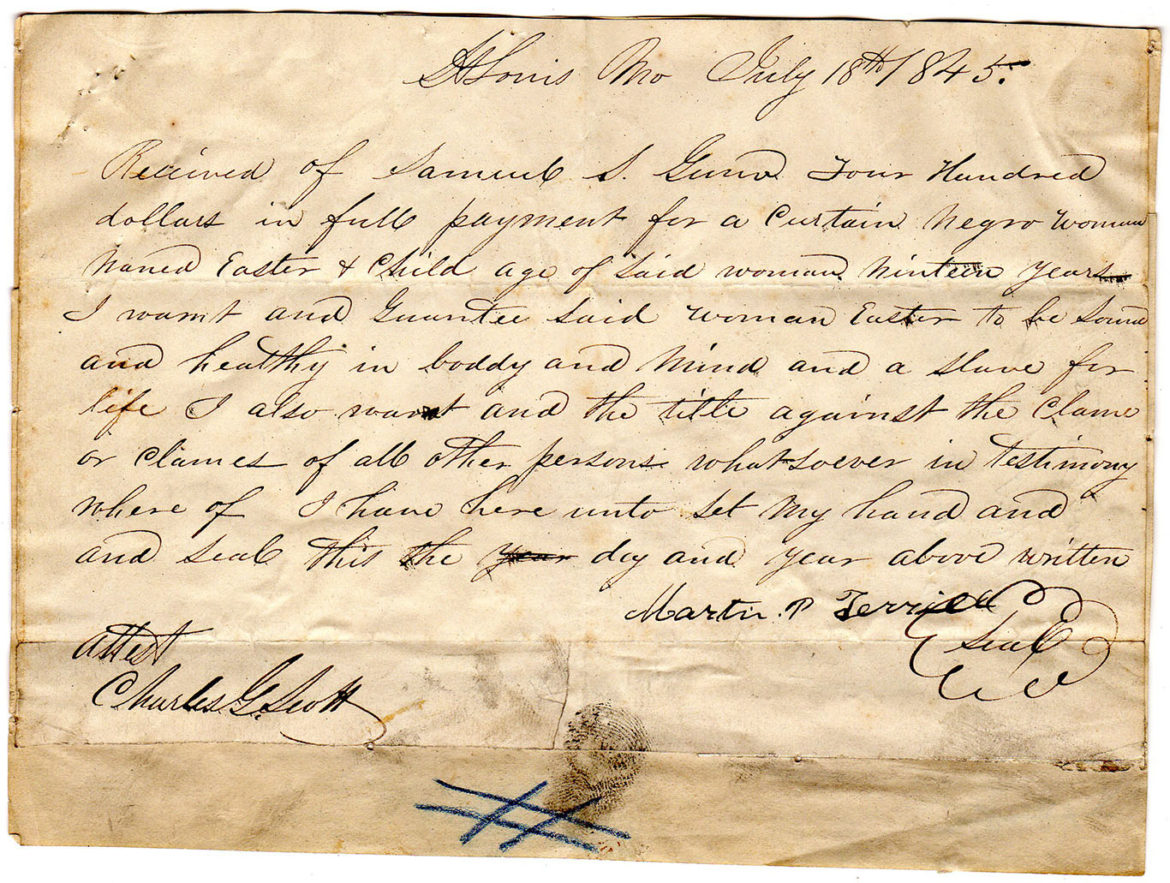

“As stated above the pathetic features of slavery were not brought home to us in the strong lights that illuminated its misery in other ways and places. To be sure when one picked up the old Missouri Republican, almost any time before the war, one would see a diminutive vignette of a run-away slave, or of another whom the sheriff wanted to see on urgent business, or, possibly, a group whose condition was a subject for discussion, if you cared to call at Lynch’s mart. This was later called the Myrtle Street Prison, and was located on the northeast corner of Fifth (now Broadway) and Myrtle streets. An illustration of the pathos is afforded in its slave-bills, a fac-simile of a real one of which is subjoined.”

I don’t doubt that Thomas was being sincere and honest when he wrote his report on slavery in St. Louis county. Still his report contains many of the features of the “ happy slave narratives” or “plantation legends” that were written by proslavery advocates before and after the Civil war. Born in 1846, Thomas was fourteen when the war broke out and eighteen when it ended. He wrote in 1911 that he had no personal knowledge of the ill-treatment of slaves in the county. I believe that he may not have been aware of it. I don’t believe it wasn’t there. I also believe that today we have a deeper understanding of the wretchedness of life as a slave than Thomas had in 1911. We also know now that millions of former slaves voted with their feet and began the “great migration” northward. Additionally DNA testing is now revealing how many of us are connected by common grandfathers. It is hard to read but the rape of the black women by their white owners is being uncovered. Many of the culprits are being identified.

In a section titled, “The Chasm Bridged”, Thomas quotes from an article published in the Globe Democrat on April 16, 1911. “The promptness and the completeness with which the passions of 1861 disappeared after 1865 brought a reunited country has no parallels in any other great conflict which the world has seen. Civil wars are the fiercest of all conflicts, and their traces last longest, but for many years past the scars which our big struggle left have been obliterated.”

The scars were deeper than Thomas and the writer of the article thought. One hundred and eight years later the chasm remains unbridged.

Once again I would like to say how much I appreciate the descendants of the Sutton and Thomas families allowing me to copy these incredibly important pieces of our history and to share them with you. Doug Houser

Odd that my wife and I were just discussing the issue of race relations the other night. We had just watched Selma about the march with Martin Luther King. We were aware of it somewhat but mainly thru seeing the news and looking at Life and Look magazines. She grew up in Kirkwood and knew about Mecham Park but as a junior high aged girl just thought it was where folks had decided to live and did not really think much more about it than that. I grew up in a small town and we had an area that we knew was where most of the black people lived. ( I apologize if this is not the correct way to refer to them but that was how we referred to it at that time. Now it is just part of the town). It was an area that had it’s own grocery store, it’s own barber shop and pool hall, a doctor and lawyer who practiced there. It was a place I went to only a few times in my 10 years of living there. Once was to take home a fellow football player during a heavy rainstorm, another was to play pool with the same football player at his dad’s pool hall.

I grew up thinking this was all just fine, that I did not make the people live like this in these different locations, have their own lives. So I think it is a real mind shift to suddenly be told this is all wrong and needs to be changed. I had no real idea what my football player friend thought of Martin Luther King or what he was trying to do. For us at the time it was so far away and about all we seemed to be concerned about was the next football game or the next test in school or which girl looked the prettiest. I suppose we could have talked about it but never did.

And like the observation by the author’s account all was fine with the way it was with the slaves. I thought all was fine with my friend’s life. But I was white and he was not and I am sure the views of things were probably much different for both of us.

Mark, I appreciate you writing this recollection. I think you have spoken very well for many of us. We realize now how much we weren’t aware of. Thanks for this.

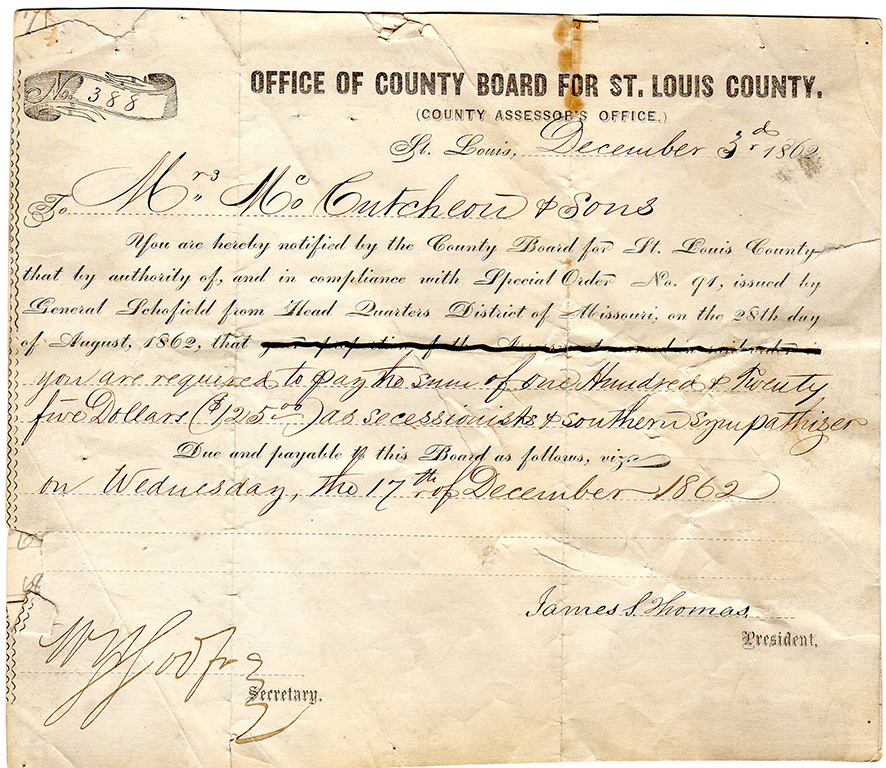

How were sympathizers and non-sympathizers going to be distinguished from one another in order to compel payments only from the former group?

Hi Tom, It must have been a sticky wicket, to say the least. On page 100, in a section titled, ‘The Men Who Went South”, Thomas writes, “Martial law had been declared very early in 1861 and those men who left the county had to go with the utmost secrecy as to their methods of eluding the eyes and guns of the home guards, who paced the banks of the Missouri river; watched the Meramec in the vicinity of “Rebel Bend” (now called Crescent); or guarded the Franklin County line. … Among those whose identification with the county and with the Confederate army life is believed to be indisputable are: (Here Thomas lists about 107 names, some that are familiar local names of streets, such as : George Bowles, Reid and James McKnight, Thrip Reavis, William and George Smizer, Dave, Mark, Joe, and George Sappington, Theodore Tesson and Dick Woodson.

He also lists William T. McCutchan, who may have been the husband of the Mrs. McCutchan to whom the above tax is directed. Thomas’ mother was a McCutchan as well. Thomas also lists his own brother, Philip H. Thomas who had disappeared in 1898 and had never been found despite much effort and money spent looking for him. Your question is an excellent one. Thanks for asking.

So possibly those who fell into the category of sympathizers may have included his own mother’s family? Interesting. And I like hearing old nicknames like “Rebel Bend.”

You have some very good advice, Pickett. During the effort to restore Woodside, I invited the lead architect at White Haven to come over to Woodside and give me some advice on how to proceed. This he did. His name is Al O’Bright. He was at that time, 2005, the historic preservation architect of the National Park Service for the midwest states. He couldn’t have been nicer. My dream was for Woodside to get a White Haven type of makeover on the way to becoming our community museum. I regret that this didn’t happen but I don’t regret trying. I met many fine people like Al along the way. I appreciate the tip about Christopher Gordon. I’ll try and make it a point to meet him. You are very welcome. Thanks for commenting.

In regards to removing slaves, etc. I think it would be enlightening to consult with the Grant Home folks at White Haven (National Park). Their staff have researched much and or worked with researchers, etc. on this topic. Plenty of abolitionists in our area too. Also, the head librarian & resarcher at the Missouri Historical Society is a font of information. Just heard him speak on his new book, Fire, Pestilence, and Death: St. Louis 1849, Christopher Gordon. Just fascinating!

Thanks, as always, for doing this and keeping us informed!!